If we are sure of one thing about the PRRS disease (Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome), it is that what we know about immunity to the PRRS virus sometimes throws up more questions and uncertainty than answers and solutions, and even, in some cases, what we know about this topic may not help us to control it effectively.

Difficulties in fighting against the PRRS

From an immunological point of view, we find that PRRS virus strains can be related in different ways to the porcine immune system, and likewise, it may be the case that the humoral and/or cellular response that can be generated, as is well known, does not necessarily have to cross-react between strains.

What is more, as if that were not enough, there can be many differences in individual and/or population response between animals after infection. All of which makes it difficult for us to predict what could happen to those animals and to our farm.

Of course, we all know and fear the havoc a PRRS infection can wreak on a pig farm. Be that as it may, it is often not possible to decipher, at least at the outset, exactly what problems it will create on our farm - respiratory problems, reproductive problems, co-infections, any of them, all of them, mild or severe?

As mentioned, the clinical symptomatology caused by PRRS has a high variability, mainly due to several causes, such as the genetic diversity of the virus, the age of the affected animals, the established immunity, secondary infections, the environment and management of the farm, established biosecurity measures, the structure of the farm, neighbours, etc., all of which complicates our ability to assess the level of protection that our animals could have against this infection.

Immunity against the PRRS

As far as knowledge about the immune response to PRRS virus is concerned, it is true that a great deal of progress has been made, but there is also clearly a shortfall of knowledge. All of which leads us, in some cases, to the situation of not knowing why our pigs fail miserably to protect themselves, while our neighbour's animals protect themselves perfectly -or vice versa of course.

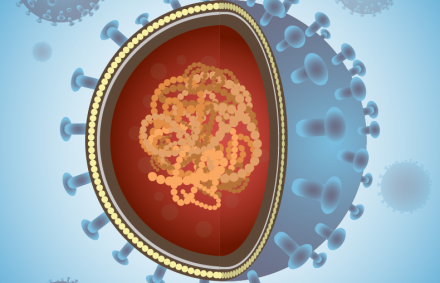

We know that there can be a low initial immune response to infection, which allows the PRRS virus, to invade tissues such as the lymphatic and pulmonary like a Viking warrior, infecting and 'taking over' macrophages and dendritic cells, which will end up as an acute infection, but which can turn into a persistent one, causing this undesirable 'guest' to linger for a long time in our livestock.

Pigs that are infected produce a rapid humoral response, but this army of antibodies created as a response is ineffective in combating the enemy, and, therefore, does not provide the expected protection. Conversely, they may act as a Trojan horse, facilitating the viruses' entry into macrophages.

So the invaded populations must wait from the fourth week of occupation for a well-armed army to arrive, with neutralising antibodies, to be able to fight the enemy more effectively, especially to avoid infection.

Even though, however, in turn the generation of the cellular immune response measured as IFN-γ-producing cells -in other words, the reinforcements for this second army- may not keep up with their battle companions in controlling the enemy.

Moreover, as particular as this infectious agent becomes, it is capable of modulating the host's immune response, inhibiting the production of certain cytokines that are important in immune mechanisms, or conversely, it can induce the production of other cytokines that are regulatory in immunity, which can lead to the failure of the cellular immune response to develop properly.

Likewise, failure to mount such an immune response may also contribute to these conquerors remaining "hidden" in the lymph nodes for a long period, so that during this time, viral shedding may occur.

What could this variability in PRRS Immunity imply?

In light of the above, we can thus have on our PRRS-infected farm a veritable potpourri of pig types.

- Animals not yet infected.

- Animals in the process of infection.

- Animals with obvious clinical evidence of PRRS, secondary diseases and/or agents that are taking advantage of the immunosuppressed situation.

- Animals with little or no evidence of illness.

- Animals in PRRS virus shedding phase.

- Recovered animals and, therefore, already protected.

- Carrier animals.

Can I help the immune system?

There is no doubt that, in order to combat the PRRS disease, we need to find a way to generate a rapid, strong and adequate immune response to seek to reduce the period of viraemia and avoid persistent infections. The goal is to stabilise the farm and keep the enemy at bay!

The use of vaccines is one more measure in the fight against this disease, as immunisation is generally a way of preventing and controlling infections by stimulating the immune system and establishing a protective immune response to the potential infection, and thus attempting to reduce the problems that the disease may cause.

However, as far as PRRS is concerned, it has unfortunately been observed that, despite its many years of existence in the pig industry, the response to vaccination against it has been very mixed.

So we can, on the one hand, support the immune system to develop a protective immunity (vaccines, immunomodulators), but we must also help the animals and our farm, through the combination of a series of measures, as discussed in the previous blog, to control, stabilise and/or, if possible, eliminate this infection from our farms.